Historic Groton Massachusetts Audio Walking Tour

Welcome to "A Rebel Town: Groton’s Revolutionary War Sites," an immersive audio walking tour created by the Destination Groton Committee to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the start of the American Revolution.

Local historian Joshua Vollmar researched, wrote and will be your guide on the tour as you explore Groton, Massachusetts — a town whose rich history was pivotal during America's struggle for independence. Groton stood prominently as a community where ordinary citizens, including minutemen ready to march at a moment’s notice under the leadership of Colonel William Prescott, courageous women who guarded against British spies, and Black residents seeking freedom, actively shaped history. Colonel Prescott played a critical role in leading local minutemen, notably commanding American forces at the iconic Battle of Bunker Hill.

This free, self-guided tour includes 16 stops: the first 10 are easily accessible on foot within Groton's town center, while the final 6 stops are best reached by car or bike, though a few are within a 10-minute walk from the center. Each stop includes a brief, informative audio segment lasting 4 to 5 minutes, and while you of course can listen at your own pace, the entire tour can be comfortably completed in under two hours.

For your convenience, each location has a dedicated Google Map link, allowing you to effortlessly obtain walking or driving directions right on your mobile device. Start scrolling down below and enjoy discovering how this small New England town played a crucial role in shaping the history of the United States.

A Rebel Town: Groton’s Revolutionary War Sites

A tour created for the 250th Anniversary of the beginning of the Revolution in 1775

Walking stops

Driving stops

Introduction

Audio Transcript

Imagine that it’s 1775. The global and local have collided right here in New England to spark a war that will change the world. During this crucial period of history, actions taken locally by people of all walks of life decisively shaped the future. And Groton was at the forefront – a rebel town in Revolutionary times.

I’m Joshua Vollmar. I’ve been researching, writing, and speaking about the remarkable history of this Massachusetts town for years. I’d like to take you on a tour of the sites that capture Groton’s contributions to the American Revolution. From the minutemen who marched to battle on April 19, to the women who guarded against spies, to Black residents who fought for freedom that had been denied them, to Col. William Prescott who commanded the American forces at Bunker Hill, the history of Groton captures the full spectrum of the moment which set in motion the nation’s founding. It is more than inspirational; it’s vital.

You can listen to this self-guided audio tour in the order of your choice. We’ve outlined a recommended route, beginning with sites in the town center that can be reached on foot, and continuing with locations best reached by car. Of course, there are far more sites of interest than can be covered on one tour, but we hope that these stories give you a picture of Groton in the Revolution.

This tour was made possible by a grant from the Groton Commissioners of Trust Funds. We extend our thanks to everyone who contributed.

First Parish Church

Address: 1 Powderhouse Road

Parking/Directions: Street parking can be found along Main Street, with a limited amount along Lowell Road in front of the church, and on the opposite side of the common along Powderhouse Rd.

Audio Transcript

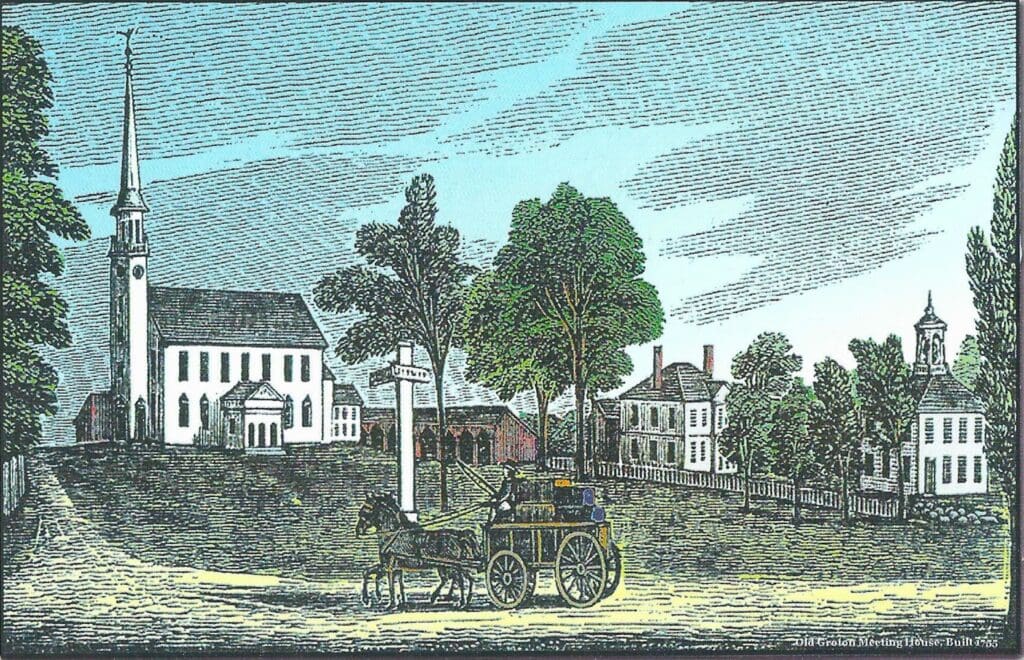

This was the center of the Groton community in the Revolutionary era. Built in 1755, the church – called a meeting house because any and all town gatherings took place here – was given its present appearance in 1839. Here, townspeople met to discuss the Revolutionary crisis. Town governments in colonial Massachusetts had a great deal of power. They regulated everything from who could live in town, to the money sent to the state, to who served in the militia. Thus, the idea of the British government halfway around the world taxing them without their consent was anathema to Groton and other communities in the Massachusetts countryside – they believed that they had always governed themselves and they always should. Unlike ports that had economic ties to Britain, there was little to connect these towns to their colonial overlord. That’s why Revolutionary sentiment first reached a fever pitch in communities like Groton, as people determined to defend what they saw as their sacred right to self-government.

As early as 1765, following the Stamp Act, the town, meeting here, passed a strongly worded resolution against the British government. This was one of the first official condemnations of British policy passed by any government in the colonies. Describing the situation as “this alarming crisis, when the American subjects of Great Britain are universally complaining of unconstitutional innovations,” it urged all actions necessary “so that posterity may never have reason to charge the present time with the guilt of tamely giving away the unalienable rights and privileges of the people of this province.”

This resolve was written by Oliver Prescott – a name we’ll hear more of. Groton in the Revolution was led by the Prescott brothers – James, William, and Oliver. They were the wealthiest people around, and constantly held leadership positions throughout the state. The Prescotts were the most influential family in the Massachusetts countryside during the war.

In 1773, a town meeting here in the meeting house voted to create a three-member Committee of Correspondence for the town. Across the state, these committees formed the backbone of the developing Revolutionary network. Groton’s consisted of James and Oliver Prescott and Josiah Sartell, who commanded one of the town’s militia companies. But like other Revolutionary leaders, these three men preached liberty but did not practice it, as all held enslaved people.

The Revolutionary crisis came to a head in 1774, when following the Boston Tea Party, the British government suspended many rights of colonists in Massachusetts, including their local government. In protest, the colonists held their own, illegal assemblies, essentially setting up their own government outside of British control. For Middlesex County, the head of that nascent government was James Prescott.1

With the colonists stockpiling weapons, the stage was set – and the First Parish Church continued to witness every step along the way, even giving up the lead weights in its windows halfway through the war to be used in making musket balls.2

References

1 This content is derived from prior research conducted by the author, and published in: Joshua Vollmar, “Groton's Revolutionary Legacy: How the Prescott Family Led Groton and The Region Through the American Revolution,” Groton Herald, September 6, 2024.

2 Caleb Butler, History of the Town of Groton, Including Pepperell and Shirley, from the First Grant of Groton Plantation in 1655 (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1848), 259.

Minuteman Common

Address: 1 Powderhouse Road

Parking/Directions: Same parking as the First Parish Church (the Common is in front of the church).

Audio Transcript

The common in front of the meeting house was the town gathering spot during the Revolutionary era. In the years leading up to the war, it was where the local militia drilled. As tensions increased in the fall of 1774, the state’s rebel government recommended that at least a quarter of militia troops should be ready at a moment’s notice to meet at a designated rendezvous point – they soon became known as minutemen.

Groton had one company of minutemen, one company that was half minutemen and half not, and two other militia companies. The designated rallying point for all was the common. Here, they would receive any needed supplies from the town’s stores before proceeding on their way.

The minutemen of the region were part of the regiment of Col. William Prescott, who lived in Pepperell, then a district of Groton. The remainder of the militia were in the regiment commanded by his brother, Col. James Prescott of Groton. Officers of the companies were elected by the troops. For Groton, Capt. Henry Farwell led the company composed solely of minutemen, while Capt. Asa Lawrence led the mixed company of minutemen and militia, and the two other militia companies were led by Capt. Josiah Sartell, who was also on the town’s Committee of Correspondence, and Capt. John Sawtell, whose company was from the north end of town, including men from Pepperell. Groton men also served in Pepperell’s company of minutemen, under Capt. John Nutting.3

Aside from training, the companies met here at the common for gatherings, such as one on February 21, 1775, a mere two months before the war began, when patriot preacher Samuel Webster of Temple, NH, addressed them in a sermon that was shortly printed and became a rallying cry for the American cause. He exhorted them to “put on the christian armour, ‘and fight the good fight of faith’ – and then … you shall assuredly triumph – in death ye shall conquer,” and “you shall enjoy the noblest freedom.”4

On the morning of April 19, 1775, after receiving the alarm that the British Army had advanced towards Concord, all the militia companies rallied on this common, later named Minuteman Common in honor of their actions that fateful morning. Capt. Farwell’s company of 55 minutemen was the first to prepare and depart. The town’s selectmen, including Oliver and James Prescott, Asa Lawrence, and Josiah Sartell had gathered and were distributing any needed supplies from the town’s stores here on the common. The minutemen, trained to be prepared, needed little, but all the town’s militia responded, and thus supplies were distributed to 94 Groton men that morning, 44 of whom were minutemen. In total, 185 Groton men marched towards Concord that day, making up well over 10% of the population of the town. 81 of those were minutemen, and 14 had responded without officially being in a company.5

Col. William Prescott, the commander of the minuteman regiment of the area, organized his Pepperell troops so quickly that when they marched into Groton, some militia members were still receiving supplies, causing William’s brother Oliver to quip, “This is a disgrace to us!”, even though the Pepperell men also needed to be armed.6

Capt. Farwell’s company, which was the first to depart early that morning, made haste to Concord, where they arrived just after the British Army had begun their retreat. They caught up with the British regulars along the Battle Road, and took part in the skirmish at Bloody Angle, the first troops from as far west to arrive.7 As one British soldier wrote after the battle, “it seemed as if men came down from the clouds.”8 With other minutemen, they chased the regulars as far as Lexington. One member of the company, Corporal Amos Farnsworth, wrote in his diary that the British regulars were “forced to retreat tho’ they [were] more numerous than we. And I saw many Dead Regulars.”9 The war had begun.

References

3 The information here can all be found in Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 2-4, 11-12, 18-20, 27-29, 31-33, 36.

4 Henry Ames Blood, The History of Temple, N.H. (Boston: George C. Rand & Avery, 1860), 310, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_History_of_Temple_N_H/KCUwAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1; Gary Shattuck, Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786-1787 (Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing and Enterprises, 2013), 141-143.

5 Green, Revolution, 11-12, 18-20, 27-29, 31-33, 36, 116-120. The numbers given here are calculations from the muster rolls and supply distribution list printed by Dr. Green. Considerable cross-referencing was needed to check these numbers. First, it should be noted that the names of five Groton men appear on two muster rolls. Asa and Joel Porter and Ezekiel Nutting (sometimes listed as Jr.) appear on the rolls of both Capt. Asa Lawrence’s militia company and Capt. Josiah Sartell’s company. Research reveals that Asa and Joel Porter were brothers, and there were no others of those names in the Groton area, and thus they must be duplicates. For Ezekiel Nutting, Ezekiel Sr. was still alive, but was 55 years old, and thus it does not appear likely that he would have been in a company. Thus, Ezekiel Nutting Jr. is assumed to have been a duplicate as well. The name of Winslow Parker appears on the rolls of both Capt. Josiah Sartell’s company and Capt. John Nutting’s company of Pepperell minutemen. Genealogy shows that there was no other Winslow Parker in the area, so this must have been a duplicate; since minute companies were more tightly monitored, it is assumed that he was a minuteman. Similarly, David Archabald (or Archibald) appears both in Capt. Farwell’s company and on an extra list tacked onto Capt. John Sawtell’s company. Once again, genealogy reveals only one David Archabald in the area at the time, and thus this is also a duplicate; as Sawtell’s addendum list was subject to questionable memory, and because Capt. Farwell’s company kept better records, it is assumed that Archabald was a member of the latter, and thus a minuteman. So, from an initial total of 178 Groton militiamen marching on April 19, the five duplicates reduce the number to 173. Additionally, after referencing the supply list, we find that two men ostensibly of Groton in Sartell’s company, William and Eleazar Spaulding, were actually of Pepperell, further, reducing the total to 171. But 14 Groton men who were not in a company were also listed on the supply roll, and thus can be added to the total, bringing it to the final of 185.

For the supply list, duplicates again must be removed. The number of duplicates shows the confusion of that morning; some men may have come back when they realized they needed more supplies. Nehemiah Holden, John Ames (sometimes Jr.), John Lawrence, and John Hugh(s) appear twice, while Jonathan Woods appears three times. Although Obadiah Jenkins was listed twice, this is most likely Sr. and Jr., as both were in Capt. Farwell’s company. Under the Pepperell men, Samuel Gilson appears twice. The proportion of minutemen and those not in a company on the supply list was determined by cross-referencing it with the five muster rolls from April 19, listing the companies of Capt. Farwell, Capt. Asa Lawrence, Capt. Josiah Sartell, Capt. John Sawtell, and Capt. John Nutting.

This calculation is imperfect based on the somewhat scrambled nature of some of the records. For genealogical references, see “Ezekiel Nutting Jr. (1751-1830),” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LC8H-F7N; “Asa Porter (1756-1852),” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LWM9-24V; “Winslow Parker (1755-1812),” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/99W2-SHR; “David Archabald (b.1743),” Family Search, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LDST-1JQ.

6 Shattuck, Artful and Designing Men, 146-147. It should be noted that Shattuck’s interpretation of the morning in Groton is incorrect. He assumes that the companies being armed on the common at the time William Prescott arrived were minutemen, and thus accuses Groton of having a slow response time. However, it’s clear that the town’s minutemen had already departed, and were the only soldiers from as far west to take part in the fighting that day. Thus, the troops seen by William Prescott were militia, who were not required to be ready at such a short notice.

7 John R. Galvin, The Minute Men: A Compact History of the Defenders of the American Colonies, 1645-1775 (New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1967), 184, https://archive.org/details/minutemencompact0000unse; David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 226. Fischer is adamant that the skirmish at Bloody Angle should be called Bloody Curve, its original name. However, the National Park Service, which stewards the site as part of the Minuteman National Historical Park, retains the name Bloody Angle, which is why it is used here.

8 Peter Force, ed., American Archives: Fourth Series (Washington, DC: M. St. Clair Clarke & Peter Force, 1837), 2: 359, image 180, https://archive.org/details/AmericanArchives-FourthSeriesVolume2peterForce.

9 Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1897-1899, series 2 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1899), 12: 78, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Proceedings_of_the_Massachusetts_Histori/4_BEAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=farnsworth. The spelling in the quote was corrected.

Site of the Powder House

Address: In front of 39 Powderhouse Road

Parking/Directions: The powder house site is roughly in the middle of the road in front of 39 Powderhouse Road. It is best to walk from the First Parish Church down Powderhouse Road. Lawrence Academy’s parking is not available for public use.

Audio Transcript

Although no trace remains today, the top of this hill was one of the most important places in Revolutionary Groton. The town’s powder house, or “magazine,” as it was called at the time, was a key storage location for military equipment. Built beginning in 1772 and completed by 1774, it was a stone building, initially twelve feet square. When constructed, it would have stood alone on this hill, shortly named Powder House Hill after it. The structure was built on land of Capt. Benjamin Bancroft, a longtime Groton resident who lived at the base of the hill along Main St.

The powder house took on a vital role in 1775. As tensions escalated, the rebel government began stockpiling weapons and ammunition in towns like Concord. A few days before the war began, Paul Revere delivered a message to Lexington on April 16, containing a warning that the British Army might soon be moving to take these stockpiles. The state’s Committees of Safety and Supplies, the latter including Groton leader Oliver Prescott, were meeting in Concord, and when this news reached them, they voted to disperse much of what was stored in Concord. Vitally, four of eight cannons and a large amount of ammunition were to be moved to the Groton powder house, under the care of Col. James Prescott, Oliver’s brother.10

The cannons arrived in Groton on the evening of April 18, creating quite a stir. An emergency meeting of the town’s militia was called. Nathan Corey, then a young man, later recalled that he was plowing a field when he got word; he immediately went home, got his gun, and went into town, where the men were debating whether to go to Concord at once. A vote was taken, and the majority favored waiting for more information.

But Corey and a few of his comrades, numbering about 9, decided to go anyways. As told by Corey, they traveled through the night by the light of torches, arriving in Concord around daybreak. They soon joined with the militia organizing there, and were in the ranks that swept down the hill towards the British regulars at the North Bridge, witnessing the “Shot heard ‘round the world” and the beginning of the war, the only men from as far west to be present.11

As the war went on, the Groton powder house remained a key storage location of military supplies, managed by Oliver Prescott, who quickly climbed the ranks to become the second highest-ranking officer in the state, with the rank of Major General. In July 1777, the state Executive Council, of which Prescott was a member, voted to increase the size of the powder house to hold 500 barrels of powder, so it was made twenty feet square, and the barrels were shortly deposited. A guard of a corporal and four privates was posted, increased after a few months to a sergeant and nine privates. These men were handpicked by Prescott to assure they were “attached to the American Cause.”

To supply the powder house, a powder mill was built on the Nashua River in what is now East Pepperell, then part of Groton.

As the war was winding down, in 1780, the state released control of the Groton powder house back to the town, which continued to store powder there for several years. After losing its purpose, it remained as a decaying reminder of the Revolution until the summer of 1829, when it was taken down.12

References

10 Virginia A. May, Groton Houses (Groton, MA: Groton Historical Society, 1978), 162; Virginia A. May, A Plantation Called Petapawag: Some Notes on the History of Groton, Massachusetts (Groton, MA: Groton Historical Society, 1976), 148-151.

11 Green, Revolution, 285-291. Dr. Green repeats an account published by William Wheildon of Corey’s story, and the evidence that supports it. In the 130-plus years since this was published, further examination of primary sources has borne up the account, and the fact of a group of Groton minutemen participating in the Battle of Concord may be considered as settled fact. However, the identities of the other members of the group besides Nathan Corey remain in doubt. It has been claimed that Abraham Childs was part of it, but he lived in Waltham at the time; it has also been suggested that Job Shattuck was, but muster rolls from April 19 show him marching from Groton that morning.

12 May, Plantation, 150; Green, Revolution, 231-240.

Prescott Common

Address: Corner of Old Ayer Rd. and Main St.

Parking/Directions: Street parking can be found along Main Street, but not at the Old Ayer Rd. junction. It is also possible to park at the trailhead for the Bates Conservation Land and walk up Old Ayer Road.

Audio Transcript

This monument is a reminder of the most influential family of Revolutionary-era Groton: the Prescotts. A dynasty with significant power in Massachusetts before, during, and after the war, they had deep roots in Groton. Benjamin Prescott and his wife Abigail Oliver were the leading citizens of the town and surrounding region in the early 1700s and lived in a house a stone’s throw from here on the right side of Old Ayer Road. Benjamin was a prominent politician and wealthy landowner, but he died at age 42 in 1738.

His three sons, James, William, and Oliver, who were all born here, were the Revolutionary aristocrats who helped lead the state through the war. James lived most of his adult life in a house that no longer stands about a quarter mile down Boston Road from here, while Oliver, a Harvard-trained physician, built the largest colonial period house in Groton directly across Main Street from here, which burned in 1815.

Both James and Oliver held high military and political rank throughout the Revolutionary period. Before the war began, James was recognized as the leader of the movement in Middlesex County, and Oliver would eventually become the second highest-ranking military officer in the state. As sheriff of Middlesex County during the war, James oversaw homeland security, while both served on the Board of War that managed all war-related activities, and Oliver served on the Executive Council that assumed the duties of governor, an office that was vacant during the war.

But it was middle brother William who achieved the greatest fame. As a young man he moved to what would become Pepperell, although it was still considered part of Groton up through the Revolution. He was colonel of the northern Middlesex regiment of minutemen at the outbreak of the war, but his fame was earned through his actions on one day: June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The day before, American commander Artemas Ward of Shrewsbury, who was a cousin-in-law of the Prescott brothers, sent William with 1,000 soldiers to build fortifications on Bunker Hill in Charlestown, fearing that the British, who had been trapped in Boston since April 19, would soon make an assault. Prescott decided Breed’s Hill was a better strategic location, and overnight, his men turned it into a fort. The next morning, the British commander Thomas Gage, alarmed, asked Americans loyal to the British if they knew the commander. One said he knew the commander well, for Prescott was his brother-in-law. Abijah Willard of Lancaster, who was married to the Prescotts’ only surviving sister, stood on the other side that day, reflecting the divisions in families seen throughout the Revolution. “Will he fight?” asked Gage. Willard replied, “Yes, that man will fight hell, and if his men are like him, you will have bloody work today.”

Indeed, Prescott, who was in sole command of the American forces that day, was a key reason their morale held. Early on, many were ready to run as the British pounded the hill with cannon fire, but Prescott, with his commanding figure, jumped on top of the earthworks, walked down the length, called to his men, and tipped his hat to the British in the harbor. With an ammunition shortage, Prescott shouted “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” although he didn’t coin it. After repelling the first two British charges, the American forces ran out of supplies. The third charge saw hand-to-hand combat, with Prescott, one of the last men in the redoubt, parrying bayonet thrusts with his ceremonial saber as he retreated.

Fifteen men from Groton were killed in the battle, the largest number from any town, including James’s son Sergeant Benjamin Prescott. However, the British lost far more, and William Prescott’s bravery demonstrated that the Americans would fight, and could do devastating damage against superior forces. Bunker Hill proved definitively that the colonies would never return to their prior status.13

References

13 For more on the Prescotts, see Joshua Vollmar, “Groton's Revolutionary Legacy: How the Prescott Family Led Groton and The Region Through the American Revolution,” Groton Herald, September 6, 2024.

The Groton Inn

Address: 128 Main Street

Parking/Directions: Street parking is available along Main Street. Public parking can be found behind the Prescott Community Center at 145 Main Street. Parking at the Inn may only be used on a temporary basis.

Audio Transcript

Today’s Groton Inn is a replica of the old Inn that burned in 2011, which had a history stretching back to before the Revolution, when part of it was built as the home of Rev. Samuel Dana around 1762. Rev. Dana was the minister of Groton’s one and only church right next door, a position that made him a community leader. However, as the Revolution drew near, he was uncomfortable, feeling that any armed resistance to British policies would have dire consequences for the colonists.

As the situation was coming to a head, Rev. Dana decided that he had to make his feelings known, and on Sunday, March 8, 1775, he preached what became known as the “Windy Sermon,” because of the weather that day. In it, he advocated nonresistance to the British government.

But this was a month before the war began, and Groton was a rebel town. The Sunday after the Windy Sermon, Dana was barred from entering the church. Anger mounted when word was released that he had refused to sign a statement that he would not oppose the American cause, and around the time the war erupted on April 19, shots were fired into his house, endangering him and his family. Shortly thereafter, a town committee met with Dana and demanded that he step down as minister and sign the statement; in return, they offered protection for him and his family. With no choice, Dana agreed, but some townspeople wanted to force him to admit to wrongdoing as well, which he never did.

Loyalists like Rev. Dana were rare in Groton and nearby, but across the nation thousands fled to places like Nova Scotia over the course of the war. The human toll of the Revolution was neighbor turning on neighbor, sibling on sibling, and permanent exile for many.

After Rev. Dana moved to Amherst, NH, his house here was bought by Jonathan Keep, who opened it as an inn during the closing days of the war in 1781. It quickly became a town gathering spot, which it remained for generations.14

References

14 Caleb Butler, History of the Town of Groton, Including Pepperell and Shirley, from the First Grant of Groton Plantation in 1655 (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1848), 123-124, 175-182; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1887), 1: no. XIV, 21-25.

Quails House

Address: 164 Main Street

Parking/Directions: Street parking can be found along Main Street and Station Avenue.

Audio Transcript

The elegant Federal style house seen here today was built in 1811 for prominent lawyer Luther Lawrence, son of a Groton minuteman. But part of the rear wing is an older house tied to the Revolution.

Before the war, it was owned by John Williams, who fought at Bunker Hill, and later became a captain in the Continental Army, serving as recruiting officer for a regiment. This was a key job as the war went on, with fewer men willing to leave their homes and businesses, especially for protracted periods. After the war Williams was a founding member of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, a social organization of veterans.

At the outbreak of the war, the house was home to Charles Quails, a tailor, who later ran the first-known bakery in Groton here. But it was his wife, Susanna, who served the Revolutionary cause.

In the weeks leading up to April 19, 1775, many women in the Groton area were concerned about the lack of a plan to defend the area in case the minutemen marched off to war. Once that fear became reality, a group of about 30 or 40 took matters into their own hands. Led by Prudence (Cummings) Wright of Pepperell, they formed an informal militia company, which became known as Prudence Wright’s Guards. Gathering whatever weapons they could find, they dressed in clothes borrowed from their husbands and brothers to fool any who might see them from a distance. The second-in-command was Sarah (Hartwell) Shattuck, whose house is another stop on this tour.

Susanna Quails was a member of the Guard. Knowing that there might be British spies in the area, the Guard decided to keep watch over a vital transportation corridor: Jewett’s Bridge, one of the only bridges to span the Nashua River, and a key route south from New Hampshire. It was located where the Pepperell Covered Bridge is today but was in Groton at the time.

The Guard remained by the bridge for several nights; on one of those evenings, two figures approached on horseback, coming down from New Hampshire. Seeing the group, one turned around, but the other was stopped and searched. British dispatches heading to Boston from Canada were found in his boots. He was soon identified as Capt. Leonard Whiting of Hollis, NH, a notorious loyalist.

It was later claimed that Prudence Wright, while visiting a loyalist brother in Hollis, overheard a conversation with Whiting in which plans were discussed to bring a British force to Groton, as the town was a key rebel stronghold.

The Guard delivered Whiting to Groton leader Oliver Prescott, and he was kept in the town lockup, earning this band of heroic women a place in history as some of the first to perform military service for America.15

References

15 Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Parker to Williams, October 15, 1770, bk. 70 pg. 524; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1893), 3: 445; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1897), 4: 319; Caleb Butler, History of the Town of Groton, Including Pepperell and Shirley, from the First Grant of Groton Plantation in 1655 (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1848), 430; Samuel A. Green, Epitaphs from the Old Burying Ground in Groton, Massachusetts (Boston: Little, Brown, 1878), 66, 68; Mary L. P. Shattuck, Prudence Wright and the Women Who Guarded the Bridge, Pepperell, Massachusetts, April, 1775, 3rd ed. (Pepperell: 1964), 35-36, https://www.pepperellhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/PrudenceWright.pdf.

Lawrence-Tarbell House

Address: 11 Court Street

Parking/Directions: Limited street parking can be found along Main Street, Willowdale Rd., and Court St., but it is best to park on the street closer to Town Hall (173 Main St.) and walk.

Audio Transcript

Home to a notorious loyalist, the Lawrence-Tarbell House has changed in both appearance and location since the Revolution. It was moved here in 1844, but originally sat on the north corner of Main and Court Streets, looking diagonally across the intersection. When it was built in the early 1700s, not only did Court Street not exist, Main Street from here to Elm Street also did not exist, as it was not laid out until 1797. During the Revolutionary era, the town’s main road flowed into what is now Hollis Street.

At the beginning of the war in 1775, this house was home to Samuel Tarbell Jr., who was descended from a family that had lived in Groton since the town’s early days. But unlike his neighbors, and notably, his brother-in-law minuteman captain Henry Farwell, Tarbell was loyal to the British crown – fiercely loyal. Not long after the war broke out, he vanished from town. It did not take long for people to find out where he went: he became the only Grotonian to enlist in the British Army during the Revolution.

So how did Groton respond? The town confiscated Tarbell’s real estate. Massachusetts had enabled towns to take property belonging to loyalists who had left the state, and Tarbell fit the bill.

But to everyone’s surprise, at the end of the war, Tarbell returned home. The law directed that, should a loyalist return, a portion of their property, including their primary residence, had to be given back to them. With that, Tarbell resumed his residence in this house, but was never at peace with the town.

Tarbell found another battle when the extension of Main Street was proposed in the 1790s, as the proposed route would go right through his property, dividing his house and barn. Vehemently opposed to this, Tarbell threatened to shoot the first man who tried to take down his fence to build the road. But before work began, he passed away, so we don’t know if he would have carried out the threat. The road was built as planned.16

Tarbell’s story serves as an important local reminder of the animosity generated by what some have termed America’s first civil war.

References

16 Francis M. Boutwell, People and Their Homes in Groton, Massachusetts in Olden Time (Groton, MA: 1890), 18; Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 223-224.

Richardson Tavern Site

Address: 264 Main Street & 5 Legion Rd.

Parking/Directions: There is very limited street parking on this section of Main Street. The closest public parking is in front of Legion Hall, 75 Hollis Street.

Audio Transcript

The busy intersection of Main and Elm Streets was quite different during the Revolution. Roads were in different places, and in place of the old Baptist Church was the town’s largest inn, a community gathering spot later called Richardson’s Tavern. No negative connotation was meant by this term, and tavern was interchangeable with inn. The large inn was divided into pieces and moved away around 1840, before the church was built, but a small part of it remains next door at 5 Legion Street.

From 1757 to 1778, the inn was run by Moses Child, a man who was fully in support of the Revolutionary cause. Integral to the community, he supplied both newspapers that shared word of the Revolutionary cause and liquors to boost the spirits of his fellow patriots. As the war drew near, he took on an active role, serving on Groton’s Committee of Inspection, charged with ensuring stores were not selling imported goods as part of the American tactic to boycott British businesses. Later, he served on the vital Committee of Correspondence for the town.

During the war, he was a Captain in the Continental Army. His most significant role came in November 1775, when he and one other person were commissioned by George Washington for a secret mission – they were to travel to Nova Scotia and find out if that colony was in support of the American cause, and what military resources they had. The mission showed that Nova Scotia was loyal to Britain, vital intelligence in the early days of the war.

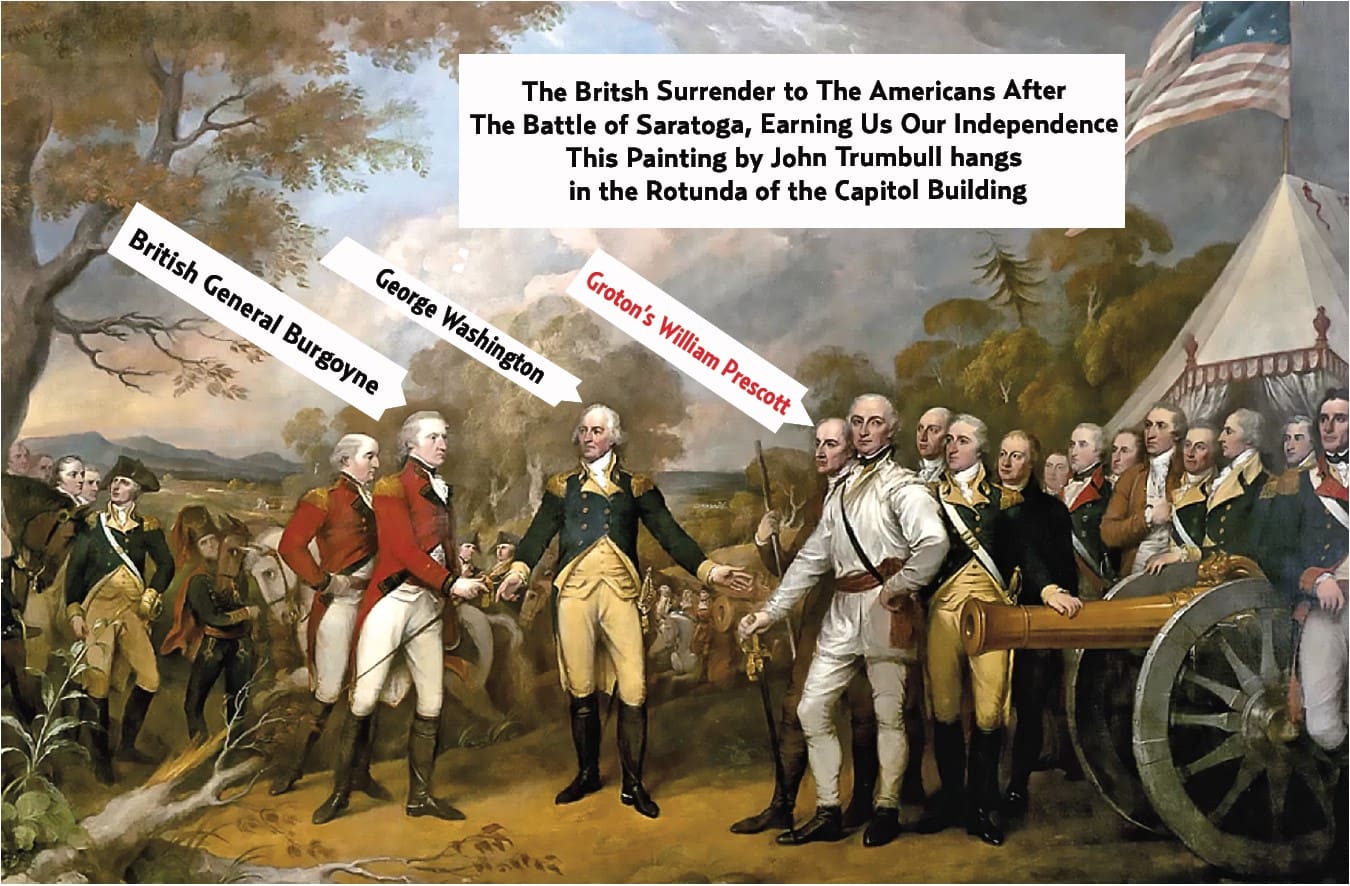

Child remained in military service for a few years, and in 1777, he was present for the surrender of British general Burgoyne following the Battle of Saratoga in New York, the turning point of the war.

The inn here was bought by Jephthah Richardson, another captain in the Continental Army, in 1779. His father built the house across the road at 255 Main Street. Ironically, Richardson’s greatest honor in 25 years as an innkeeper was to host a British royal, the father of Queen Victoria, in 1794.17 Americans disliked British policies, but still liked their style.

References

17 Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Trowbridge to Child, November 16, 1757, bk. 55 pg. 167; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Child to Mitchell, April 1, 1778, bk. 78 pg. 382; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1893), 3: 349-352; Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 109-111, 123, 134, 151, 196; Samuel A. Green, Facts Relating to the History of Groton, Massachusetts (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1914), 2: 131-132; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Tufton to Richardson, January 23, 1779, bk. 80 pg. 420; Alan L. Whipple, Academy Days, Groton Days, Vol. 1 (Westford, MA: Murray Printing, 1985), 224-225; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1890), 2: 360-361.

Swan House

Address: 25 School Street

Parking/Directions: Public parking is available in front of Legion Hall, 75 Hollis Street.

Audio Transcript

This house was built around 1771 for William Swan, a wealthy merchant who ran a store on the property. At the outbreak of the Revolution, Swan, unlike many of his neighbors, did not immediately march to war, but after a couple years, he found that the wartime economy made it impossible to run his store, and so joined the army.

Swan’s story reflects the path of the war. After beginning in Massachusetts in 1775, when many Grotonians were directly involved, it moved south and west. Grotonians that served later in the war took part in efforts such as the Rhode Island Campaign of 1777-1778, battles in New Jersey following Valley Forge, and defending Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga in upstate New York in 1776 to 1777, when the British launched an invasion from Canada seeking to divide New England from the other states.

At Fort Ticonderoga in 1776, Capt. Zachariah Fitch of Groton, the namesake of Fitch’s Bridge, led a company of men who made the arduous march from this area to upstate New York, only to find that the fort was filled with illness. One member of the company, Nehemiah Parker of Groton, caught the so-called “Camp Fever” and soon passed away.

The next year, another Groton company, led by Capt. Job Shattuck – whose house is a stop on this tour – came to replace Capt. Fitch’s troops. They were met with the same conditions. At one point, Ensign Amos Farnsworth was the only officer of the company fit for duty.18

It must have been demoralizing for these men and others present when the British Army surrounded the fort, forcing the Americans to retreat and abandon it without a battle.

This sudden setback led to a call for more troops, and William Swan answered, forming a company that marched to Saratoga. Others from the area, including Col. William Prescott, the hero of Bunker Hill, also rushed to help, and several were present when British General John Burgoyne surrendered his army – Barzillai Lew, a Groton native and one of the most distinguished Black men in the Continental Army, provided the music for the occasion. Prescott appears in the famous painting of the event, which proved to be the turning point of the war, as it paved the way for an alliance between the Americans and the French.

In 1778, William Swan, after returning to Groton, became the commander of the Groton Artillery Company, one of the first artillery companies in the state, and was shortly promoted to major. This company was noted as the second oldest in the state at the outbreak of the Civil War and was one of the first to see combat in that conflict.

Swan sold this property in 1779 to William Bant, who retired from a career managing the Boston mercantile house of founding father John Hancock, who had affixed American’s most famous signature to the Declaration of Independence.19

As seen through this one property, the Revolution permeated every facet of life in Groton throughout the war, hardly diminishing with the close of hostilities in 1781 and even the official peace treaty in 1783.

References

18 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 51-62, 70, 279; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1893), 3: 177-178.

19 Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1893), 3: 96-98, 177-178, 253-254; Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 301; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Swan to Bant, February 10, 1779, bk. 80 pg. 134; William Bant Account Book, Baker Library Special Collections and Archive, Harvard Business School, Allston, MA, https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/11/resources/11399.

Old Burying Ground & Old Town House Site

Address: 75 Hollis Street

Parking/Directions: Public parking is available in front of Legion Hall, 75 Hollis Street.

Audio Transcript

The Old Burying Ground is the final resting place for scores of Revolutionary War soldiers and sits near the heart of the colonial village of Groton. Nearby, on the site of Legion Hall, was the old Town House that contained the town’s lockup, which held loyalist Leonard Whiting after he was captured by Prudence Wright’s Guard with British dispatches in his boots.

The Burying Ground, which was used from about 1680 until the early twentieth century, holds innumerable stories, and is the resting place of many mentioned in this tour. The stones show their age, but here can be found Groton minutemen who responded on April 19, 1775, including Henry Farwell and Asa Lawrence; militia leaders like John Sawtell; men who embodied the American contradiction of liberty and slavery like Josiah Sartell; heroic women of Prudence Wright’s Guard, such as Susanna Quails and Sarah (Hartwell) Shattuck; and the towering Prescott brothers, James and Oliver.20

Also here are those who were moved to Groton after contributing to the Revolutionary cause. Notable among them is Capt. Abraham Childs, who lived in Waltham when the war began, and was a minuteman who fought on April 19 and Bunker Hill; a Continental Army officer who crossed the Delaware with Washington and fought in the Battle of Trenton; assisted in the Saratoga campaign at the turning point of the war; suffered through Valley Forge; and led the charge in the morale-boosting capture of the British fort at Stony Point, NY, in 1779. Nearby to Childs is Joshua Bentley, later related to him through marriage, who rowed Paul Revere across the Charles River prior to his midnight ride.21 The glen quietly echoes with history.

References

20 For records of the Old Burying Ground, see Samuel A. Green, Epitaphs from the Old Burying Ground in Groton, Massachusetts (Boston: Little, Brown, 1878).

21 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 251-254; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1897), 4: 257.

Site of Captain Farwell's House

Address: 2 Farmers Row

Parking/Directions: Limited street parking is along the common at the corner of Pleasant Street and Farmers Row, on the leg in front of The Elms (108 Pleasant St.).

Audio Transcript

A monument marks the area that was the homestead of one of Groton’s most steadfast Revolutionary War soldiers. Henry Farwell purchased this property in 1760, and would live here until his death in 1804, in a house that stood a bit south (to the left) of the present brick house, which was built in 1837. Groton historian Caleb Butler described Farwell as “a man of small stature, but very strong and athletic, and of undaunted courage.”

Farwell, like many Grotonians, had fought in wars prior to the Revolution on the side of the British, who were expanding their empire in conflict with the French and Native Americans. Because of his experience, Farwell was chosen captain of a company as the Revolution drew near – but not just any company. Farwell was in command of the only company in Groton composed entirely of minutemen, 55 in total, making it the largest such company northwest of Concord.

Farwell’s company formed the first line of defense, and on April 19, 1775, were so quick to prepare that they were able to make the approximately 20 mile march to Concord in time to catch up with the retreating British regulars at Bloody Angle on the Battle Road around 1pm, when the alarm only reached Groton sometime around 6am, and it took 3 hours for the men scattered throughout the town to be alerted and assembled. Their record proves why the moniker ‘minuteman’ was appropriate for these soldiers – they were truly ready at a moment’s notice.

Farwell’s record grew more impressive during the Battle of Bunker Hill. One Groton man under his command, Samuel Lawrence, whose house is a stop on this tour, later told the story of how Farwell was wounded in the battle. A musket ball passed through his body and lodged near his spine. When a man came to carry Farwell away after he was shot, word was passed along that he was taken for dead. As told by Lawrence, “This report brought back the captain’s voice, and he exclaimed, with his utmost power, ‘It ain’t true; don’t let my poor wife hear of this; I shall live to see my country free.’”

Later, during the retreat from the hill, Capt. Farwell seems to have lost some of his spirit, as when brothers William and Jonas French of Dunstable ran across him while retreating, he said to them “I cannot live. … Take care of yourselves.” Even so, they carried him to safety. Following the battle, the bullet was removed, and Capt. Farwell recovered. Rather morbidly, he kept the musket ball as a souvenir, engraving “1775” onto it, and passed it on to his descendants, as well as a carved powder horn. His sword was even featured on “Antiques Roadshow.”

Remarkably, Farwell returned to service after his injury, and continued to lead his company throughout the rest of 1775, although he was never in another battle. His heroics in 1775 meant that he did live to see his country free, as he proclaimed at Bunker Hill. His death in 1804 occurred within a week of the passing of Asa Lawrence, who commanded the rest of Groton’s minutemen on April 19, and whose house is also a stop on this tour.22

References

22 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 8-17; Amos Lawrence, Extracts from the Diary and Correspondence of the Late Amos Lawrence with a Brief Account of Some Incidents of his Life, ed. William R. Lawrence (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1855), 3-4; Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Indian Wars (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1883), 155; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1897), 4: 84, 433; David Parsons Holton and Frances K. (Forward) Holton, Farwell Ancestral Memorial: Henry Farwell, of Concord and Chelmsford, Massachusetts, and all his Descendants to the Fifth Generation (New York: D. P. Holton, 1879), 60, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_l/Y5NJAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0; Elias Nason, A History of the Town of Dunstable, Massachusetts, From its Earliest Settlement to the Year of Our Lord 1873 (Boston: Alfred Mudge and Son, 1877), 114, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/KX8lAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0; Caleb Butler, History of the Town of Groton, Including Pepperell and Shirley, from the First Grant of Groton Plantation in 1655 (Boston: T. R. Marvin, 1848), 269; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1887), 1: no. XVIII, 13; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Holden to Farwell, April 22, 1760, bk. 59 pg. 338; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Farwell to Farwell, January 10, 1802, bk. 166 pg. 205. Capt. Farwell’s sword was on Antiques Roadshow season 21, episode 12 (aired April 10, 2017), “Salt Lake City: Hour 2,” beginning around 44 minutes in.

Lawrence Homestead

Address: 44 Farmers Row

Parking/Directions: Limited street parking is along the common at the corner of Pleasant Street and Farmers Row, on the leg in front of The Elms (108 Pleasant St.). Walk from there.

Audio Transcript

The front section of this house, known as the Lawrence Homestead, was built between 1796 and 1797 for Revolutionary War veteran Samuel Lawrence, a Groton native. Lawrence was living on his father’s farm on Old Ayer Road during the war.

Lawrence was a corporal in Capt. Farwell’s company of Groton minutemen on April 19, 1775, and, as fate had it, he was one of the first to receive word of the British advance. The alarm begun by Paul Revere and his colleagues was carried by more than a dozen riders that night. It was brought to Groton and then Pepperell by Edward Bancroft, who began his ride in Acton and reached Groton around 6am. One of the first people he informed was prominent leader Oliver Prescott, who lived at the head of Old Ayer Road.

As later recounted by Lawrence’s son, Prescott “came towards the house on horseback, at rapid speed, and cried out, ‘Samuel, notify your men: the British are coming.’ My father mounted [Prescott’s] horse, rode a distance of seven miles, notified the men of his circuit, and was back again at his father’s house in forty minutes.” Thanks in part to Lawrence’s efforts, the company caught up with the retreating British forces at Bloody Angle in Concord.

Samuel also fought at Bunker Hill, where he was wounded, and later served in the Rhode Island campaign of 1777 to 1778, rising to the rank of major. During his first furlough in July 1777, Lawrence decided to marry his fiancé, Susanna Parker, after his mother said something to the effect that if anything happened to him, it would be better for her to be “his widow than his forlorn damsel.” But during the wedding ceremony at the First Parish Church, the alarm bells rang, calling soldiers to duty, and Samuel had to leave immediately after the couple was pronounced man and wife.

Samuel lived to see much happen after the war. His sons became great industrialists, some of the wealthiest people in the country, and later the namesakes of Lawrence Academy and the city of Lawrence, MA. One of them, Amos, was the largest contributor and most dedicated fundraiser for the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown. Samuel saw the cornerstone of this great obelisk placed before his death in 1827.

As for the Lawrence Homestead, it remained in the family and was expanded greatly in 1876, forming a reminder of the minuteman who founded a dynasty.23

References

23 Amos Lawrence, Extracts from the Diary and Correspondence of the Late Amos Lawrence with a Brief Account of Some Incidents of his Life, ed. William R. Lawrence (Boston: John Wilson and Son, 1855), 3-4, 53-54, 121-125, 275; David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 145; Green, Groton Historical Series, 1: no. 16, 15-16, 3: 286-287, 4: 247-248, 318.

Moors House

Address: 518 Farmers Row

Parking/Directions: There is no parking near this house. Drive by to look. There is extremely limited street parking by the Moors School site (corner of Culver and Moors Roads), and additional parking can be found at the General Field, where there is also a sign about the area’s history.

Audio Transcript

Built around 1717 for Abraham Moors, this commodious house was home to his son Joseph during the Revolution. Joseph Moors fought at Bunker Hill and rose to the rank of major in the Continental Army. But he also embodies the American contradiction of liberty and slavery.

During the Revolution, many American leaders fought for their version of liberty while enslaving others. Joseph Moors was one of them. His father had enslaved a woman named Zebinah, who in 1751 had a son named Titus, who was enslaved by Joseph. Just a year before the Revolution, in 1774, Titus ran away, and Joseph posted an advertisement and reward for his return. It is unknown whether Titus was returned to slavery.24

It was also common, during the war, for enslavers to send enslaved people to fight in their stead. One Grotonian, Isaiah Edes, who moved to town after his prior home in Charlestown was burned during the Battle of Bunker Hill, chose to do this. Thus, as a captive to slavery, Charlestown Edes was a soldier for liberty, serving in the Battle of Bunker Hill and again in the Continental Army at the end of the war in 1780 and 1781. But the wages he was due for his service were paid instead to his enslaver, and he had no choice but to return to slavery at the end of his service.25

How was the contradiction justified? One reason is that the liberty American leaders referred to was the freedom of a society to govern itself, not the individual freedom we think of today. There was also a clear distinction based on race and national origin, with Revolutionary leaders claiming rights based on their status as white, male citizens of colonies like Massachusetts, that had been granted certain governmental rights in their initial charters.26

But there were many who fought in the war and interpreted these promises in a different way. We have some local examples. Two free Black men, Cato Frye and Pomp Phillis, enlisted in the Continental Army under Groton’s quota, although neither lived in town at the time.27

Another example is Barzillai Lew, a Groton native, whose parents were both enslaved in town but had bought their freedom by the time he was born in 1743. After growing up in town, he moved to Pepperell and later Chelmsford, from where he served in the Revolution. He was famous in his day as a musician and served as the company fifer, a vital role for coordination. At Bunker Hill, he kept morale high by playing “There’s Nothing Makes the British Run Like Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and served with distinction at Ticonderoga. When British general Burgoyne surrendered at Saratoga, the turning point of the war, Lew was chosen to play the music for the procession and ceremony. After the war, he moved to a farm in Dracut, founding one of the most influential and longstanding Black families of the area.28

In the end, the Revolution did usher in a form of freedom for the enslaved people of Massachusetts. The state adopted its constitution in 1780, and the bill of rights contained in it caused multiple enslaved people to sue for their freedom. In 1783, the Supreme Judicial Court decided that the State Constitution had outlawed slavery; the 11 enslaved people living in Groton at the time finally had their freedom.29

References

24 See Joshua Vollmar, “Reflections on Juneteenth,” Groton Herald (Groton, MA), June 23, 2023.

25 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 90, 93-96, 171.

26 See David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 28-29.

27 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 25-26, 82, 126.

28 “Barzillai Lew,” Freedom’s Way National Heritage Area, https://freedomsway.org/story/barzillai-lew/; George Quintal, “Barzillai Lew,” Boston National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/barzillai-lew.htm. It should be noted that most Groton historians, including the first, Caleb Butler, and the second, Samuel A. Green, recorded the story of the Lew family, reflecting their prominence.

29 Samuel A. Green, “Slavery at Groton in Provincial Times,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1909), 42: 200-202, https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/RxPmWxPdX1cC?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Captain Asa Lawrence's House

Address: 245 Lowell Road

Parking/Directions: There is no parking near this house. Drive by to look. The closest parking is street parking along Shattuck St., but it is dangerous to walk this section of Route 40 (Lowell Rd.)

Audio Transcript

The main part of this house was built about 1773 for Asa Lawrence, who shortly embarked on a distinguished military career in the Revolution.

At the outbreak of the war, Lawrence was captain of a Groton company composed half of minutemen and half of militia. It was unusual for companies to be mixed like this, with only some of the men ready on a moment’s notice. Because of that, Lawrence’s company did not catch up with the retreating British Army on April 19.

But they took the next chance to show their bravery. The second battle of the Revolution, which occurred on May 27, 1775, before Bunker Hill on June 17, is called the Battle of Chelsea Creek. While mostly forgotten today, it was a morale-boosting American victory, and Asa Lawrence played a leading role.

At the time, American forces were attempting to secure land and resources around Boston Harbor, while the British were holed up in the city. A detachment of forces, led in part by Capt. Asa Lawrence and including several Groton men, were dispatched just after midnight on May 27 to round up cattle and destroy resources that could be used by the British on Noddle’s Island and Hog Island next to Chelsea.

The British were alerted later in the day, and the schooner Diana was sent up Chelsea Creek and began to bombard the militiamen, while British troops came ashore to pursue them. Amos Farnsworth, a Groton soldier, wrote, “we had a hot [fire] until the regulars retreated.” The schooner Diana continued to fire on the American forces throughout the day, but as the tide receded, it lost its ability to maneuver and called for help. The American forces began an assault, and the British crew soon abandoned ship. Capt. Lawrence led the charge on board, and the American forces took everything of value, particularly the cannons. Then, as Farnsworth wrote, “we [set] [fire] to [her] and Consumed [her] there.”

The cannons taken from the schooner were used at Bunker Hill, where Capt. Lawrence commanded a company, and he brought back one with him to Groton, where it remains today.

Capt. Lawrence later fought in Rhode Island and New York. But, in a sign of the economic distresses of the time, he was not paid for his service, which, in part, led him to sell this property.30

When he sold this house in 1777, it was purchased by James Sullivan, who lived here for five years. Sullivan, the brother of a general in the Continental Army, was a lawyer and politician who moved here from Maine, then part of Massachusetts. He had been involved in the Revolutionary government of Massachusetts since before the beginning of the war. While living here, in 1779, he was selected as Groton’s delegate to the convention that wrote the influential Massachusetts State Constitution. Then, in 1782, he was chosen as a delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in place of none other than Samuel Adams. He later served as attorney general and then governor of Massachusetts.31

The Revolutionary connections of this property continued after Sullivan sold it in 1782, as it was purchased by Nathan Davis, who moved from Concord, where he had fought in the famous battle on April 19 as a minuteman. He later became a captain in the Continental Army. In 1795, Davis sold the house to Capt. James Lewis, who relocated from Billerica, where he too had been a minuteman who fought in the Battle of Concord.32

Few properties can boast such a range of influential Revolutionary era residents.

References

30 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 5-6, 18-26, 59, 136-137, 145-146, 152, 155, 158, 184, 204-205, 209, 211, 229-230, 247, 249, 258, 279; Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1897-1899, series 2 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1899), 12: 80-81, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Proceedings_of_the_Massachusetts_Histori/4_BEAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=farnsworth. The cannon was found by the late Earl Carter at the Groton Historical Society and formed the centerpiece of his collection of Groton history memorabilia after he restored it.

31 Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Lawrence to Sullivan, December 14, 1777, bk. 78 pg. 325; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1893), 3: 199-201.

32 Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Sullivan to Davis, April 2, 1782, bk. 84 pg. 534; Middlesex South Registry of Deeds, Cambridge, MA: Davis to Lewis et al., March 24, 1795, bk. 130 pg. 258; Samuel A. Green, Groton Historical Series (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1897), 4: 457-458.

Job Shattuck House

Address: 573 Longley Road

Parking/Directions: There is no parking at this house. Drive by to look. Extremely limited street parking can be found opposite Paquawket Path just north of the house, with additional parking located at the trail head beyond it.

Audio Transcript

Home to Groton’s most controversial Revolutionary-era figure, this house was built about 1782 for Job Shattuck. A Groton native, his first military experience came at age 19 in 1755. By the outbreak of the Revolution, he was a lieutenant, the second-in-command of the Groton militia company under Josiah Sartell, and responded on April 19, 1775, although too late to take part in the battle. He served honorably at Bunker Hill, Fort Ticonderoga, and Saratoga, and was captain of a company beginning in 1776.33 His wife, Sarah (Hartwell) Shattuck, also performed important military service as the second-in-command of Prudence Wright’s Guards, whose story is told with the Quails House.

But it is the Revolution’s epilogue that defines Shattuck’s story. Despite America’s victory in the war, the country’s situation was anything but settled. A weak federal government left states to their own devices, and vast debts incurred because of the war left the nation in a deep depression, which, by some measures, was worse than the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Many farmers and former soldiers were in dire straits, with their military wages unpaid, their farms in worse shape than before the war, and no hard currency or credit to be had. On top of this, Massachusetts, which had taken on more debt than any other state due to the war, imposed heavy and sweeping taxes, ruining many. And financial ruin did not just mean the loss of homes, food, and clothing – it meant debtor’s prison. This was the prospect faced by as many as a third of Grotonians in the early 1780s.

Job Shattuck, at one time the town’s largest landowner, did not face these concerns personally, but deeply sympathized with those who did. Because of that, in 1781, the same year the war was won, he led a mob that stopped local tax collections in an event known as the Groton Riots, the first resistance to the new government.

The discontent came to a head in 1786. Shattuck and others concerned about the situation called an emergency town meeting and passed strongly worded resolutions aimed at stopping all debt and tax collection and revamping the financial system of the state. These measures were vehemently opposed by the influential Prescott brothers, who were aligned with the interests of the state elite.

Not long after, Shattuck led a contingent that stopped the Court of Common Pleas, which dealt with debt cases, from sitting in Concord. This heralded the beginning of Shays’ Rebellion. Shattuck’s cohorts then set their sights on the next sitting of the court in Cambridge. By some accounts, Shattuck was forced to go along with the plan against his will. But this time, the rebel force fell apart. Meanwhile, Oliver Prescott, the influential Grotonian who had sweeping executive powers, issued a request to the governor for the arrest of Shattuck, along with 2 other men from Groton and 2 from Shirley, for their role in the rebellion.

A massive military search party came to the Groton area, right on the heels of the rebels returning home after their aborted mission. In fact, Shattuck had stopped at the house of a friend on the way home that night. The next morning, the soldiers arrived to search this house, but did not find Shattuck. Later that day, they found him along the Nashua River coming back towards the house. He resisted capture and received a slash across his knee that crippled him for life.

That night, he was held in the town lockup, and townspeople were so mad that a mob formed and attempted to burn buildings belonging to local elites. Shattuck was spirited off to a Boston jail the next day, where a stacked jury found him guilty of treason and he was sentenced to death.

But the state elite had pushed too far. As the rebellion got out of hand in the western part of the state, an election turned the governor and several others out of office, including the Prescott brothers. Shattuck soon received a pardon and returned home to a hero’s welcome. Controversy has remained ever since about the rebellion, and Shattuck’s role in it.

But Shays’ Rebellion had an important effect: it convinced many nationwide of the need for a stronger federal government, leading to the writing of the U.S. Constitution in 1787. With that, the Revolution’s epilogue laid the keystone of the new Republic.34

References

33 Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900), 65.

34 Many sources discuss Shattuck’s role in Shays’ Rebellion. The most complete and balanced, which is also a biography of Shattuck, is Gary Shattuck, Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786-1787 (Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing and Enterprises, 2013).

Memorial Common

Address: Corner of Hollis St. and Martins Pond Rd.

Parking/Directions: Limited street parking can be found along the common near the beginning of Martins Pond Rd. (the one-way double-wide section).

Audio Transcript

Memorial common is dedicated to Grotonians who have fought in wars since the U.S. was founded, beginning with the Revolution. First erected on the common at the corner of Main and Pleasant Streets, these tablets were moved here in 1954.35

The Revolutionary War memorial tablet is on the Hollis Street side of the large stone parallel to Martins Pond Road. Note that it gives the years of the war as 1776 through 1781. 1776 was used because that is considered the birth of the country with the Declaration of Independence, even though the war had started the prior year. 1781 marks the end of hostilities, not the official peace in 1783.

The tablet is an attempt to capture all Grotonians who served in the Revolution and lived in town at the time of their service. Due to fragmentary records, it is not entirely accurate, but captures most of this roll of honor. 319 names are listed on the tablet. When correcting for other Groton soldiers, the total comes to 331, but this may still be off due to incomplete records. Regardless, this is an impressive roll of honor for a town which had a little over 1,600 residents at the beginning of the war.36

Also, this does not count the women of Prudence Wright’s Guard, who should rightly be included. Unfortunately, without any list of the Guard, only two from Groton can be identified with certainty: Susanna Quails and Sarah (Hartwell) Shattuck.

One more additional could be made: Samuel Tarbell Jr., the loyalist who joined the British Army. While not a popular stance, he was a Grotonian who fought in the Revolution.

With that, Groton’s total comes to 334, but is almost certainly higher.

Take a moment to look over the names, and those of Grotonians who served in other wars, and consider the human stories behind them. These were people who made decisions without knowing how the story would end, like we do in hindsight. The actions of thousands upon thousands of people like these won a war that changed the world. If you ever doubt that the world can change, or that you could be a part of that change, remember the regular Americans, and Grotonians, who stood on their principles two and a half centuries ago.

References

35 Virginia A. May, A Plantation Called Petapawag: Some Notes on the History of Groton, Massachusetts (Groton, MA: Groton Historical Society, 1976), 22, 138.

36 The following changes should be made to the list on the tablet: Eleazar and William Spaulding, listed as Groton men, were actually of Pepperell, as covered in note 5. Also, there are three duplicates on the tablet (because of the different spellings of last names): Jonathan Boyden also appears as Jonathan Beyden, John Pierce also appears as John Pearce, and Jonathan Tarbell appears with his surname spelled both Tarble and Terbol. Thus, four names should be removed, bringing the total to 314. There are a couple names that may be duplicates, but it is not clear, namely James Sheple and Shipley and John Sheple and Shipley. Also, nine names are included of men who lived in other towns, but enlisted to fill Groton’s quota: Samuel Cole, Joseph Clough, Cato Frye, Arnold Gilden, Jesse Garfield, Michael Keening, James Peirt, Samuel Taylor, and Peter Youngman. That brings the total to 305.

But names should be added as well. Oddly, the tablet does not list several officers of the Revolution from Groton, specifically (rank given is highest achieved): Major General Oliver Prescott, Colonel James Prescott, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Farrington (his son is listed), Major William Swan, Captain Moses Child, Captain Benjamin Bancroft Sr., Captain Benjamin Bancroft Jr., Captain Amos Lawrence Sr. (Amos Lawrence Jr. is listed), Captain Nathaniel Lakin, Lieutenant Oliver Parker (active in Shays’ Rebellion), and Sergeant Abel Parker. Also, some other soldiers were not listed, specifically: Ephraim Parker, Chambers Corey (killed at Bunker Hill), Nathaniel Corey, Samuel Lawrence (a private in Capt. Farwell’s company of minutemen, separate from Corporal Samuel in same company), Eleazar Flagg, Eleazar Green Jr. (only Sr. was listed), Levi Samson, Tobias Brigs, Jonas Sawtell, Benjamin Shaw, and David Williams. Also, there were multiple Grotonians who turned out on April 19, 1775, but were never officially in a company, specifically: Nehemiah Holden, Nehemiah Tarbell, Joseph Herick, and Ebenezer Patch. More could possibly still exist in the records. With those 11 officers, 11 privates, and 4 from April 19, Groton’s total comes to 331.

These revisions are all based on information from Samuel A. Green, Groton During the Revolution (Cambridge, MA: John Wilson and Son, 1900). It should be noted that the place of residence of soldiers is not always given, and so it can be difficult to determine which town they lived in.

Credits

Scriptwriter: Joshua Vollmar

Historian: Joshua Vollmar

Narrator/Voice Talent: Joshua Vollmar

Editor/Audio Producer: Ashley Doucette

Special thanks:

Commissioners of Trust Funds

The Groton Channel

Lawrence Academy

Groton School

Prescott Community Center

Groton Conservation Trust